By George Aine

Statistics indicate that since the 1950s, 8.3 billion tons of plastic has been produced. However, it is estimated that only 9% of this has been recycled, leaving 6.3 billion tons of it as waste that clogs oceans, lakes, rivers and soils worldwide.

Two university students Miranda Wang, a 23-year-old Canadian, and her friend Jeanny Yao in 2015 visited a city waste recycling plant in Vancouver, Canada where they grew up.

They observed that even the recycling being undertaken at the plant was not enough to deal with plastics crisis “because even plastics that are put into a curbside recycling bin end up being exported overseas in developing countries where they become ocean pollution.”

They then founded BioCellection and embarked on a study that would develop technology to do away with plastics altogether without recycling. They shifted their thinking towards using chemicals with a focus on film plastic.

BioCellection uses a process called pyrolysis where intense heat is applied to break down plastics so they can be reused as oils and for energy.

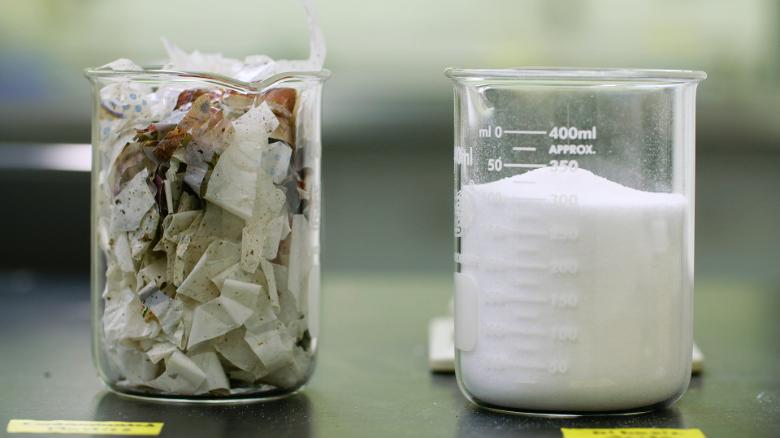

“We shred this plastic, put it into a flask and then we add our liquid catalyst,” Wang is quoted as saying by CNN. It is a relatively conventional chemical process – something she prioritised during its design so that it can be scaled.

The reaction occurs at 120 degrees Celsius in common glass equipment with no added pressure. While the surface contamination on the plastic bathes in the catalyst, it does not react. The plastic itself, made up of a long carbon chain of polymers, destabilises and collapses on itself to create other chemicals with four to seven carbons in the chain link.

Currently focusing on plastic films like shopping bags, the three-hour process breaks down plastic into chemicals that can act as the building blocks for more complex plastic products: nylon for clothes, shoe soles, even automobile parts.

“Right now, we’re able to achieve about 70% conversion from plastic waste material to these chemicals,” she adds, saying they’re working to boost that figure. Crucially, BioCellection believes that when scaled up, it could undercut the virgin plastic market.

“We believe that our process is actually cheaper than processes that currently depend on using petroleum to make these chemicals,” Wang says. “The cost reduction could be up to 30-40%.”

The company has attracted attention, and Schmidt Marine Technology Partners (established by ex-Google executive chairman Eric Schmidt and his wife Wendy) is among its supporters. BioCellection is now building partnerships with sorting facilities including Greenwaste in San Jose, along with chemical companies and brands to build their supply chain.

“My dream is to be able to see that something that is a sad piece of plastic — that would right now go to the ocean or landfill — could be used to make a brand-new Patagonia jacket or a brand-new pair of running shoes, or could be used in other industrial applications,” says Wang.