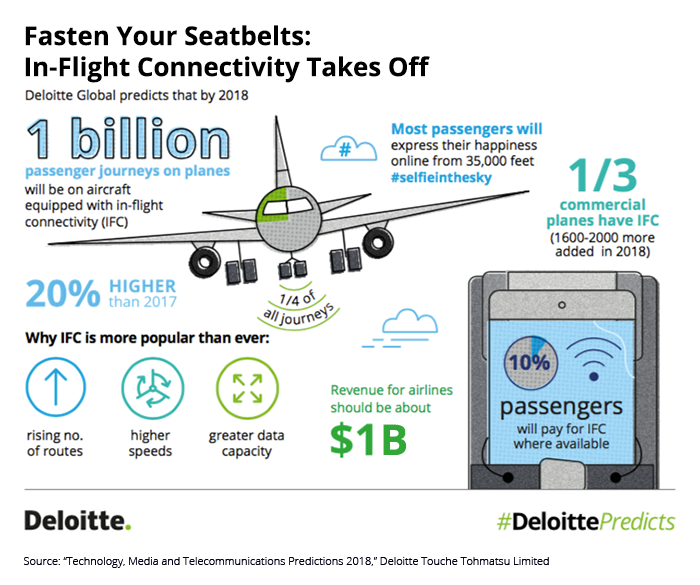

In-flight connectivity (IFC) is shaping up to be more popular and lucrative than ever in 2018, predicts Deloitte Global. Thanks to the rising number of routes covered, higher connection speeds, and greater data capacity per flight, Deloitte Global estimates that by the end of the year, around a third of all planes will have IFC and 1 billion passenger journeys—about a quarter of the total—will be made on IFC-equipped planes, representing a 20 percent increase over 2017. IFC revenue for airlines should be close to $1 billion.

Technology advances increase speeds, capacity

IFC adoption has not been as widespread as it might have been, probably because the limitations of legacy technologies affected service quality. Improvements in transmission and receiving technology should make the business case for IFC more compelling. Advances in technology for air-to-ground (ATG) and satellite transmission—the two ways to deliver IFC service—are expected to enhance the user experience, lower prices, and drive customer demand.

ATG, a network of specialized ground-based mobile broadband towers, relays signals to antennas located on the underside of a plane’s fuselage. As in a terrestrial cellular network, the plane automatically connects to the closest tower. ATG has been cheaper and has lower latency than satellite-based services, but it works only over or near land and is constrained by the available cellular spectrum.

Must read: How to minimize data consumption while using VPNs

During 2018, ATG providers are expecting to leverage LTE technology and unlicensed spectrum to deliver peak speeds of up to 100 megabits per second (Mbit/s)—about 10 times faster than existing ATG solutions—at a much lower cost.

IFC via satellite communication with rooftop aircraft antennas provides coverage across the globe—over oceans as well as over land. However, satellite-based systems typically cost more and have higher latency than ATG systems.

Many satellite providers are moving to high-throughput satellites (HTS), which employ technology that increases throughput to more than 100 Mbit/s. Compared with non-HTS satellite-based services, which deliver 10 to 70 Mbit/s to an aircraft—capacity that is shared among all passengers using the service—HTS could substantially increase capacity and data speeds while significantly lowering costs. Further growth in IFC satellite capacity is expected beyond 2018 as HTS deployment ramps up and more systems are launched.

Meanwhile, planes’ receiving technology has also improved in recent years; the introduction of flat-panel antennas has reduced drag created by legacy satellite antennas that were less aerodynamically efficient. Improvements to in-aircraft receiving technology will likely include modems that provide speeds of up to 400 Mbit/s as well as the use of multiple receivers instead of one, which can enable more consistent service.

Consumers Driving Demand

Demand for new IFC capacity could be significant. Historically, IFC use has been concentrated among business travelers, many of whom expense the fees. Leisure travelers likely have held back because of cost and quality concerns.

Today, demand for connectivity is so strong that most consumers prioritize it over other amenities. One survey found that if respondents had to select from a range of services, 54 percent would choose Wi-Fi while only 19 percent would choose a meal; another found that almost 90 percent of IFC users would trade seats or additional legroom for a faster and more consistent wireless connection.

Airlines are motivated to meet this demand, attract and retain customers, and generate revenue. Revenue could come directly from the sale of airtime or indirectly—free IFC service could spur new customer acquisition or improve loyalty, for example.

The most popular charging model is for either a set number of minutes or for the duration of a flight. Some airlines offer low-bandwidth services such as texting free of charge, while others offer no-cost connectivity for a limited period to increase service awareness and entice further usage. If IFC proves to be a revenue generator, it may allow airlines to augment the already booming market for ancillary services such as checked baggage, food and drink, and early boarding. Revenue from the top 10 airlines’ ancillary fees increased more than 13 times between 2007 and 2016.³

Still, other airlines may delay IFC deployment, given the capital cost of between $200,000 and $300,000 per plane, the revenue is forgone by grounding the plane for the three-day installation, and the ongoing cost of capacity. Some of these costs may be offset by savings realized from reducing the plane’s weight—which could lower fuel costs—and uninstalling existing seatback entertainment systems or eliminating new installations, which could remove a major maintenance cost and the expense of new entertainment systems. Some of these cost savings could be put toward purchasing capacity and media content for customers’ personal devices.

Already popular with many business travelers, IFC may be well on its way to becoming a standard in-flight feature. As technology improves and costs decrease, most passengers will likely be delighted to have always-on connectivity extended to air travel. #Selfieinthesky, anyone?

The article was written by Paul Lee, partner and head of global technology, media, & telecommunications (TMT) research, Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited; and Paul Sallomi, global TMT leader for Deloitte Tax LLP

Related:

Loon CEO reflects on bringing the technology to Kenya

How to recall a mistakenly sent email on Gmail